Designing Assignment Sheets and Grading Rubrics

Designing Course Documents

The assignment sheet and grading rubric are two important documents that make assignment requirements and assessment criteria transparent to students. These documents are closely related but communicate slightly different things.

This resource offers some ideas on what to consider when designing these important course documents.

Assignment Sheets

An assignment sheet, or prompt, should clearly communicate to students what the assignment’s expectations are. They should also be an example of what the instructor considers “good writing.” For example, if students are expected to write something concise, complete, and with an awareness of audience, the assignments sheet should do that, too. Show students the kind of writing that is expected of them!

An assignment sheet communicates what the instructor (or the discipline) values in writing. Framing it in that way can help students aim not just for a grade, but for growth as a writer in the field.

The following guiding questions can help instructors clarify what they want from students, which will help as they write the assignment sheet and can also inform the rubric’s design:

1. What should students learn from doing this assignment?

a. These should relate directly to the course objectives and outcomes.

2. What knowledge or skills should students demonstrate?

a. These should be things that have been introduced, practiced, and reviewed in class.

3. What characteristics of the final product will demonstrate that students have learned the desired outcomes?

a. It’s likely that one assignment cannot address all desired outcomes. Prioritize the most important ones.

b. These criteria can then be used to define rubric categories. E.g. a clear thesis statement, precise and concise technical writing, strong organization, etc.

Finally, make sure the assignment sheet or prompt answers all the following questions:

1. Who (Audience and writer):

a. Who is the audience?

b. What is the writer’s role? I.e. Is there collaboration involved? Are there check-ins with the instructor? Is AI allowed?

2. What (Genre):

a. What is being written, and what is necessary for this type of writing?

b. What citation format should be used?

3. When and Where (Policies):

a. When and where do students submit things?

4. Why (Purpose):

a. Why are students doing this assignment, and why now?

Rubrics

Assignment sheets give students the instructor’s expectations, and rubrics communicate how well they have met those expectations. While it may seem that the rubric re-states many of the criteria in the assignment sheet, it should be written with the goal of communicating information back to the students about their writing.

The process of designing a rubric can be a helpful way for instructors to think through how the assignment meets course goals, which will make it easier to communicate those criteria to students both in class and via the assignment sheet. Some instructors feel that grading with rubrics is more consistent and efficient.

There is enormous variability in rubrics and creating one that works for the graders, captures the goals of the assignment, and is meaningful for students is part of an iterative process of design.

Creating a Rubric

Determine a rating scale for each assignment criterion that was prioritized earlier. The most basic rubrics define what adequate and inadequate performance looks like for each category, but more descriptors can be helpful. For example, defining “outstanding” performance gives students a sense of how to go above and beyond. More descriptors at intermediate levels give students feedback on their work beyond “adequate.”

Examples of rating scales:

· Exceeds standards, meets standards, approaching standards, below standards

· Represents strong work, accomplishes the task, needs improvement

· Well done, satisfactory, needs improvement, incomplete

Next, for each category of the rating scale, describe the specific criteria. For example, if one of the assessment markers is: “The paper makes a strong argument,” define what a well-crafted argument is, then define a satisfactory one, an incomplete one, etc.

Choosing rubric types:

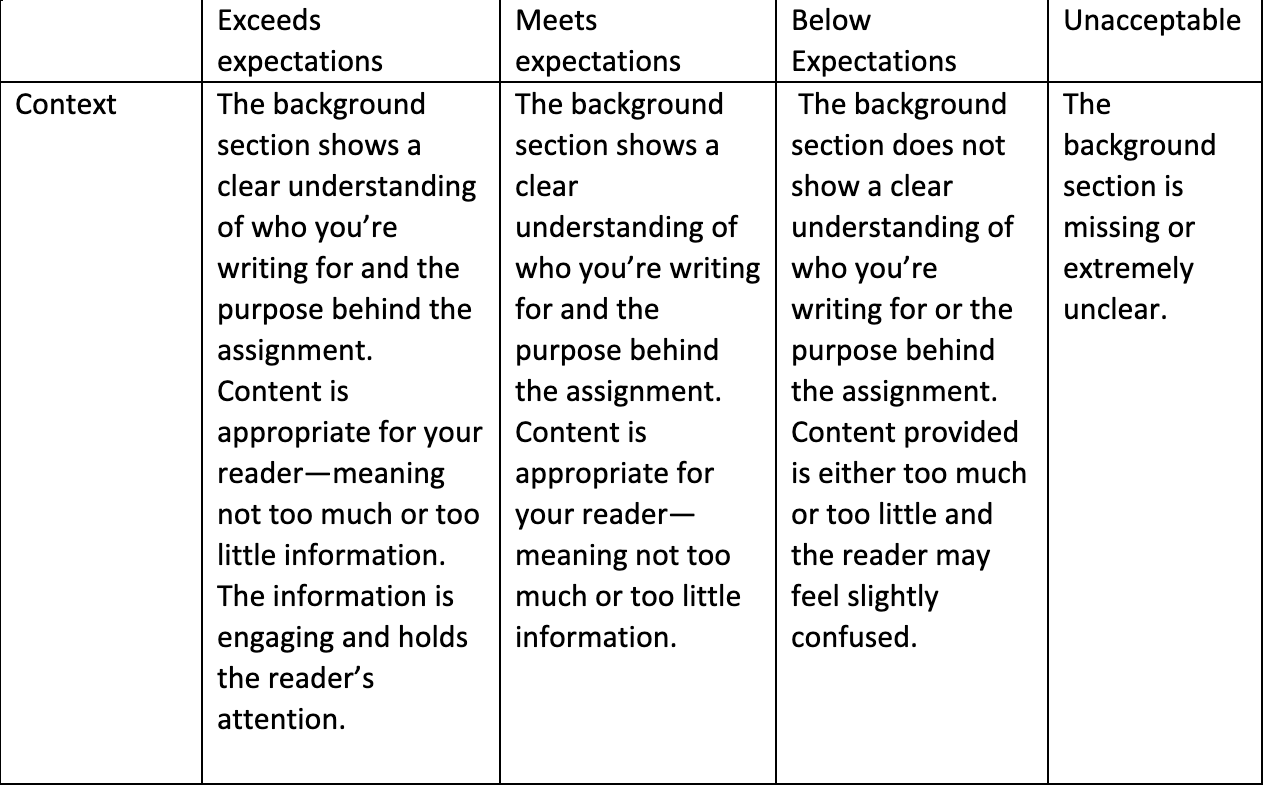

A holistic rubric provides a broad general description of the requirements for each level of performance. Multiple criteria are articulated for each proficiency level, so the student’s work will necessarily into a fairly broad category, maybe A, B, C, or D.

For example: “An A paper clearly defines the main points which are in turn well supported with evidence and references. The technical content is correct. The format is organized so that the reader can easily navigate the document. The figures/tables are presented clearly. The vocabulary use is appropriate for the reader and the document is professional in appearance and style.”

An analytic rubric has performance descriptors for each assignment criteria, which allows for more specific feedback for each area. This type of rubric may list criteria such as organization, clarity, grammar, etc. with a description of multiple levels of proficiency for each.

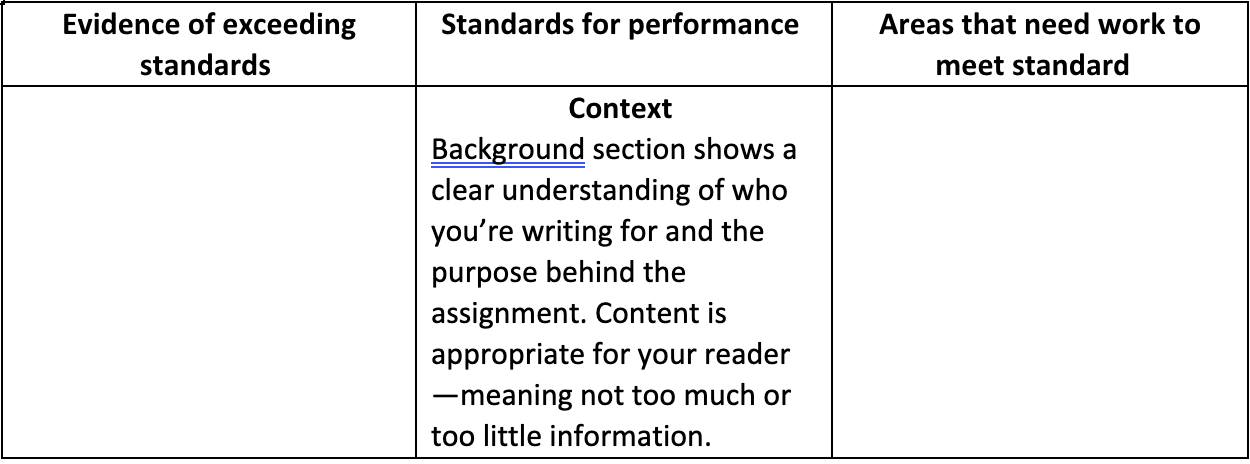

A single-point rubric is a rubric that is divided into three-columns. The middle column defines the proficiency standard for each criterion being assessed while leaving empty columns on either side of this description for the instructor to write comments on the ways in which the standards were exceeded or not met. A single point rubric allows the instructor to define the expected outcome for the assignment while tailoring feedback for each assessment category.

Revising and norming rubrics:

No rubric will work perfectly the first time. Be open to adjusting the rubric as you use it and as you get feedback from students and other graders. Over time it will become more refined.

If there are multiple graders using the same rubric (TAs, for example) take time to norm before grading the first assignment. Norming means having multiple instructors grade the same student paper with the same rubric and then talking through why each grader chose to give it the score they did. Doing this with a few student papers will help graders be more consistent in interpreting the scale and criteria.

Finally,it’s important to acknowledge that grading writing, even with a rubric, is inherently subjective. Be clear about that with students and discuss how the rubric is an attempt to make that subjectivity as transparent as possible.

Sources:

Active and Alternative Assessments: Missouri Online

How to Use Rubrics: MIT Teaching + Learning Lab

Know Your Terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics: Cult of Pedagogy

Types of Rubrics: Center for Teaching and Learning: DePaul University